Why Is the Tissue Bank So Important For Melanoma Research?

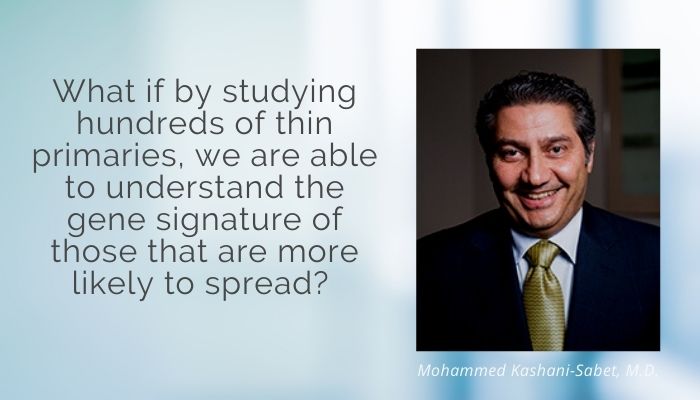

We answer this question with the help of Mohammed Kashani-Sabet, M.D., the Director, Center for Melanoma Research and Treatment; and Medical Director, Cancer Center, California Pacific Medical Center.

Dr. Mohammed Kashani-Sabet’s research through the International Melanoma Tissue Bank Consortium (IMTBC) aims to identify the difference in gene signatures between primary melanomas and benign lesions by studying a large number of fresh frozen tissues.

According to Dr. Kashani-Sabet, there are 30,000 genes in our body, which are expressed at different levels, in different tissues, and at different times. When researchers look at a confirmed melanoma and a clearly benign lesion, and they look at the patterns in the expression levels of various genes, they will find markers. “If we find the right combination of genes,” he says, “we can discriminate between a mole and melanoma much more accurately.”

It makes intuitive sense that a melanoma’s gene expression would be different from that of a benign lesion. After all, if unchecked, melanoma spreads within the body and kills you, and benign lesions stay in place and are not dangerous.

“Our earlier research shows that there is a difference in the gene expression profile for a benign mole vs. a melanoma, but we need to repeat the research on a large number of fresh frozen primary melanomas in order to understand more and to be sure. That’s what we are looking for in our research: those markers, that gene expression profile.”

His earlier work was performed using older technology, called microarray analysis, and on just a small number of tissues that were fresh-frozen. With the large number of tissues he’ll have through the IMTBC, all fresh frozen so they preserve RNA, he’ll be able to use newer technology called RNA Sequencing, which is much more powerful.

“Imagine what we can do now,” he says.

All kinds of positive outcomes could come from this work, but one of the most important might be a diagnostic test—to know quickly and easily which moles and skin lesions are potentially deadly, and which are benign.

“As a practitioner, I don’t have a reliable test,” he says. “It’s an issue.”

What he hopes to help create is a really accurate tissue test for widespread clinical use, one that is used in conjunction with a standard pathology diagnosis.

Not only would this test be helpful as a confirmation of all pathological diagnoses, but it would be even more important for the approximately 15% of melanoma cases that are not routine—those that are very difficult to classify and those about which even pathologists disagree.

When pathologists disagree on whether a patient has melanoma, it’s a problem. “How do you treat it if you don’t agree on what it is?” asks Dr. Kashani-Sabet. He also notes that ambiguous lesions are more common in pediatric cases. The conversation with parents is understandably hard when you tell them their child has cancer, “but it’s even more difficult to say, ‘I don’t know if your child has cancer’.”

Another outcome of his work could be prognostic understanding.

Think, he says, about those melanoma patients who have a very thick primary melanoma—ulcerated, with a high mitotic rate—but a Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB) that is negative. What if we could figure out the gene signature of melanomas that will spread? We would treat those patients very differently from those with a gene signature that has shown not to spread.

Or the people who have a positive SLNB, but only a few positive melanoma cells in those lymph nodes. What if we could accurately predict those who have melanoma that will continue spreading? Again, we’d treat those patients very differently.

Or the many, many people who have a thin primary melanoma—should they have a SLNB in the first place? What if by studying hundreds of thin primaries, we are able to understand the gene signature of those that are more likely to spread? For these patients we’d perform SLNB right away and continue carefully monitoring and treating the patient, and what might have in past years developed into Stage III or IV melanoma instead never progresses.

“Each of these are different subgroups,” he says, and we need to study large numbers of primary tissues in each subgroup to help answer these critical questions. The tissue bank was formed for just this purpose.

“We think that the primary tissue holds the entire genetic code. So we’ve got to study primary tissue. But before we can study it, we have to bank it. That’s why AIM’s tissue bank is so important.”

READ more about our International Melanoma Tissue Bank Consortium.