Nailing Down on the Ultraviolet Exposure Occurring During the Curing and Drying of a Manicure

by Mandi Murph, Director of Medical Education

Introduction

It’s a health risk many may not know exists – nail lamps. Nail lamps are a UV light source used during manicures and pedicures to dry polish or to harden/fix artificial nails. The lamps are only used for a few minutes at a time but leave long-lasting effects after repeated exposure.

Beautifully manicured nails symbolize health, vitality, and self-care. Yet ironically the nail lamps used to achieve this look increase the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer on the hands and feet.

Whether used at home or in salons, the UV intensity penetrating the skin from nail lamps is comparable to tanning beds, which are known drivers of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Recent research links nail lamp use to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (also called squamous cell skin cancer) and other skin cell damage. Nail lamps (sometimes called gel lamps) emit unknown levels of UV-A light and potentially small amounts of UV-B light and therefore expose a manicure client’s hands and fingers to harm.

This article gives information about nail lamps, explains differences in ultraviolet (UV) light, and provides data about the risk to those who use them during manicures. Finally, this article will provide simple strategies that manicure lovers can employ to keep their skin safe, keep nails decorated, and reduce the risk for skin cancer.

Manicures, Artificial Nail Products, and Nail Lamps

There are several different types of manicures. While a simple manicure includes trimming, filing, and polish, a more extensive manicure includes the application of artificial nails and the polish or decoration of those nails. A simple manicure with nail polish or one that applies acrylic nails might include the use of a nail lamp for drying purposes. But manicures that include the application of a type of artificial nail called gel or polygel nails must use a nail lamp as part of the fixing process.

Artificial nail enhancements such as acrylic nails, gel nails, polygel nails, and dip powder nails, are trending in the U.S. and combine for a global artificial nails market that exceeds a billion dollars. Additionally, the market for artificial nails is expected to have steady upward growth over the next ten years.1

Each type of artificial nail is applied using different chemical methods and techniques. Gel nails and the hybrid product—polygel nails—use a gel polymer that is crosslinked or fixed under a nail lamp. Gel and polygel nails are popular because the product is odorless during application, and once applied, the nails are flexible (so they feel natural), durable, and considered high-quality. Typically, gel nails last two to three weeks before they are removed, refilled, or redone.

Placing hands under the nail lamp is necessary to finish this type of manicure. Without the fixation step, the gel or polygel nail polymer will not fully cure or harden, and the product will not be set.

In addition to being used to affix gel and polygel nails, nail lamps are sometimes used to quickly dry acrylic nails or to dry the polish on a standard manicure. Acrylic nails are artificial enhancements that cover the natural nail with a hard exterior surface to decorate. They are chosen for the product’s strength which prevents chipping, is longer-lasting, and is low maintenance compared to natural nails. Acrylic nails can be embossed by trimming to different lengths or shapes, colorfully painted, and decorated with glitter, gems, or other embellishments.

Types of Ultraviolet (UV) Light Waves and Nail Lamps

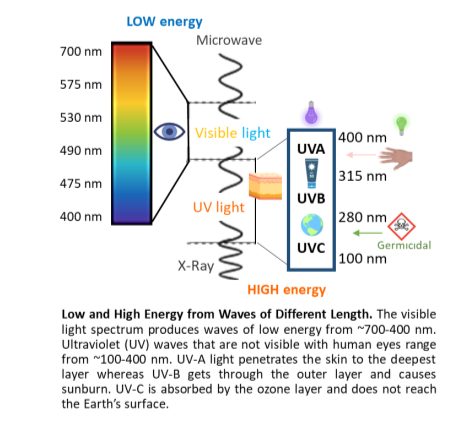

UV light can penetrate the skin and mutate human DNA. When DNA is mutated, cancerous tumors can form. In 2012, the International Agency for Research on Cancer evaluated and classified ultraviolet-emitting devices (wavelengths 100–400 nanometers [nm], encompassing UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C) as carcinogenic to humans. These wavelengths are shorter than visible light and cannot be seen by human eyes.

UV light waves come in several forms – UV-A (400-315 nm), UV-B (315-280 nm), and UV-C (280-100 nm). UV-C comes from space and is absorbed by the ozone layer protecting Earth. Therefore, this type of UV wave is irrelevant here as it does not apply to nail lamps.

In contrast, UV-A and UV-B pass through the ozone layer and reach the Earth’s surface. UV-A causes photoaging and the appearance of lines and wrinkles in the skin, while UV-B causes sunburns. Both UV-A and UV-B are linked to the development of skin cancers by causing DNA damage.

Nail lamps use either fluorescent bulbs or light-emitting diode (LED) lamps, and both emit UV light. Fluorescent lamps emit wavelengths of 410-300 nm, whereas LED lamps emit wavelengths of 425-375 nm, with peak emissions at 375 nm and 385 nm, respectively.2 The FDA notes that there is no danger to human skin from these lamps when there is at least 10 inches of distance between the lamps and human skin, such as in a typical room.3 But hands under nail lamps are extremely close to the light source and UV emission and therefore concerning.

Devices known to emit high, concentrated doses of UV-A include tanning beds, which are known to contribute to the development of skin cancer. A tanning bed is designed to emit a UV index of 12, which is the amount of UV one would experience during midday in the tropics.4 Studies evaluating tanning beds and nail lamps indicated the UV-A radiation to the skin is similar.5

Nail lamps require less than ten minutes to achieve their results, highlighting an issue: The UV exposure is concentrated and rapidly reaches an unnaturally high level at each exposure. Further, damage accumulates when exposure to artificial devices becomes routine. Indeed, patients have reported receiving blistering sunburns on their hands after salon visits for gel nails.6

Does an Agency Monitor Nail Lamps or UV Exposure?

In the U.S., no agency evaluates, standardizes, or routinely certifies the UV intensity emitted from nail lamps used in spas and salons. One study tested 17 different nail lamps from 16 salons and observed a wide range of measurements, such as intensity of UV-A emitted from the lamps and the number and type of bulbs used in each. In other words, there was a significant lack of consistency among values collected from the salons. The lack of consistency was attributed to different brands of nail lamps, bulb wattages, and the number of bulbs per device. However, the researchers found a strong correlation between the amount of UV-A irradiance emitted and a high light bulb wattage.7

Among the 17 nail lamps in the research study, the minimum UV-A irradiance was 0.6 mW/cm2, and the maximum was 15.7 mW/cm2, which is an enormous variation. Since the average time for exposure during a single visit was 8 minutes, the energy dosage each client might experience could differ dramatically.7

For example, for the lowest dose measured, over 200 visits to the salon would be required before a client reached a level sufficient to damage DNA. This damage would increase the risk of cancer but it would still be a relatively low risk over a long period of time. However, the highest dose measured in the salon study would require only eight visits by a client to reach a dangerous exposure level. At the higher dose, the DNA damage would start accumulating faster, increasing the risk for cancer to develop.7

For the lowest dose measured, over 200 visits to the salon would be required before a client reached a level sufficient to damage DNA. However, the highest dose measured in the salon study would require only eight visits by a client to reach a dangerous exposure level.

Another study on UV-A lamps may help explain why some salon visits could be more harmful to certain clients than others. The researchers observed high UV-A variability from the lamps, and prolonged exposure sufficient to induce DNA damage. More importantly, during prolonged usage, the internal temperature of the lamps increased. The temperature rise magnified the intensity of the UV-A and caused more DNA damage.8 This observation suggests that a nail lamp that is kept on for multiple clients has the potential to cause far more DNA damage to the later clients.

Reports of Cancer With UV-A as a Suspected Contributor

Research literature has numerous observational studies linking nail lamps to the development of skin cancer.

For example, one patient with nonmelanoma skin cancer on her hands and feet reported getting manicures and pedicures every 2-3 weeks for a decade. Her routine included UV nail lamp use, and she recalls receiving blistering skin damage from at least one experience at a salon. Over time, she developed eight skin tumors on her fingers and 46 precancerous actinic keratoses on her fingers and feet.9

Another patient diagnosed with skin cancer—squamous cell carcinoma—had a 15-year history of twice-monthly nail lamp exposure for acrylic nails. Three stages of Mohs surgery were needed to remove her skin cancer.10

Squamous cell carcinomas were also found on the left and right hands of another woman who used UV devices routinely. Over 25 actinic keratoses on her hands were treated with cryotherapy. There were no other skin lesions or suspicious areas on her entire body—just her hands. This diagnosis came after an 18-year history of UV nail lamp use every three weeks at a salon.11

Dr. Julia Curtis, a dermatologist in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Utah only sees the occasional patient with skin cancer possibly associated with manicures or pedicures. One patient “had manicures and pedicures for most of their adult life, and they were developing skin cancers on their hands and feet. It’s concerning,” she recalled.

Further, Dr. Curtis said, “There has certainly been an increase in the amount of people using UV nail lamps recently. We don’t have the data yet, but in 10-15 years, we could see a spike in terms of skin cancer around the hands and feet.”

A surprising report suggests that decades of exposure are not necessarily required for skin cancer to appear. One patient diagnosed with several squamous cell carcinomas on both hands visited a nail salon eight times in one year before her cancer appeared.10

It is not understood why there is so much variation between the timing of exposure and cancer between the cases, but the level of genetic risk for an individual can be a factor (more on this topic, below). Additional environmental and occupational exposures could also be factors. And it cannot be presumed that a case of skin cancer appearing on the hands was caused solely by UV nail lamps.

Further complicating the subject is the fact that some literature has shown the risk of nail lamps to be negligible. It is no wonder the general public reports confusion about this topic.

Individual Risks and Medications Causing Photosensitivity

Not all individuals bear the same risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer. In addition, any risk for cancer is not a guarantee – it’s a possibility. Even among families with a very strong history of disease, there is likely to be a surviving member who was never afflicted by the disease.

Individuals with a moderate to high risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer include those with a family history of skin cancers, individuals with fair complexions, people with photosensitivity disorders, and patients who are immunosuppressed. People at the highest risk have a genetic susceptibility to developing skin cancer.

Groups at the highest risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer are most at-risk to damage from nail lamps and other UV exposures because of their susceptibility. Unexpected or unknown factors, such as medications, could combine to further increase their risk.12

Medications that suppress the immune system after an organ transplantation are a known risk factor for developing skin cancer, yet other lesser-known medications may have a similar effect. Some prescribed and over-the-counter drugs can cause a user to become more sensitive to the effects from UV waves.

Some antihypertensive drugs are photosensitizing, which would magnify the intensity of UV exposure. Danish studies, for example, suggest that the risk for squamous cell carcinoma increases with long-term use of the diuretic hydrochlorothiazide, which is prescribed to treat high blood pressure or edema.13,14

Other drugs such as oral contraceptives that contain estrogen and progestin increase photosensitivity.15 In addition, prescription antibiotics like tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and sulfonamides are photosensitizing. Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs also belong to this category. Acne medications like prescription retinoids and topical creams can also increase light sensitivity or cause photocontact dermatitis.16

If someone with a lower risk of skin cancer takes photosensitizing medications before UV light exposure, their natural barriers will be diminished and their risk increases. They become sensitized to the effects of UV light.

Recommendations for a Safer Manicure

A simple recommendation is not to use nail lamps or use them as infrequently as possible. If you get standard manicures or even acrylic nails, tell your manicurist that you’d like your nails to dry naturally.

But if it’s important to you to have routinely manicured gel nails or polygel nails which require use of a nail lamp consider some additional strategies for long-term healthy skin. You can employ several steps to protect your skin from the UV rays emitted from a nail lamp.

Apply a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen of SPF 30 or higher to the hands and fingertips before a manicure that includes nail lamp use.17,18 Another option recommended by dermatologists and doctors is to wear UV-A protective gloves, which will act as a barrier to the UV rays.7

When it comes to at-home manicures, you have the power to minimize UV exposure. Choose LED lamps over fluorescent ones for less UV-A exposure. More importantly, turning off the nail lamp after each use can significantly reduce the increase in UV-A emitted from temperature elevations.8

Even if you are convinced that your risk for skin cancer is exceedingly low, UV-A does more than cause indirect DNA damage. Repeated exposure causes photoaging in addition to DNA damage. Taking preventative measures can therefore reduce unnatural skin aging.

Following these safety measures can help you keep your hands and fingers safe from the UV light emitted by nail lamps. Treat your skin well so that it can last a lifetime. Be informed, be smart about UV exposure, and follow a simple concept: Be polished and protected.

References

1. Global Artificial Nails Market Report Coverage. Spherical Insights. 2023. www.sphericalinsights.com /reports/artificial-nails-market. Accessed July 30, 2024.

2. Shihab N and Lim HW. Potential cutaneous carcinogenic risk of exposure to UV nail lamp: A review. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2018;34(6):362-365. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12398.

3. Federal Drug Administration. Compact Fluorescent Lamps (CFLs) – Fact Sheet. Accessed 8.13.2024. https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emitting-products/home-business-and-entertainment-products/compact-fluorescent-lamps-cfls-fact-sheetfaq

4. International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. https://monographs.iarc.who.int/list-of-classifications. Accessed August 5, 2024.

5. Wilson J and Maraka J. Need for sun cream with your manicure? Dangers of UV nail dryers. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(6):871. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.03.011.

6. Freeman C, Hull C, Sontheimer R et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the dorsal hands and feet after repeated exposure to ultraviolet nail lamps. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(3):13030/qt1rd1k82v.

7. Shipp LR, Warner CA, Rueggeberg FA et al. Further investigation into the risk of skin cancer associated with the use of UV nail lamps. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(7):775-6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8740.

8. Finn E, Dussan L, Rosenthal S et al. Temperature Is a Key Factor Governing the Toxic Impact of Ultra-Violet Radiation-Emitting Nail Dryers When Used on Human Skin Cells. Int J Toxicol. 2024:10915818241268617. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1177/10915818241268617.

9. Freeman C, Hull C, Sontheimer R et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the dorsal hands and feet after repeated exposure to ultraviolet nail lamps. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(3):13030/qt1rd1k82v.

10. MacFarlane DF and Alonso CA. Occurrence of nonmelanoma skin cancers on the hands after UV nail light exposure. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(4):447-9. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.622.

11. Ratycz M, Lender JA and Gottwald LD. Multiple Dorsal Hand Actinic Keratoses and Squamous Cell Carcinomas: A Unique Presentation following Extensive UV Nail Lamp Use. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11(3):286-291. doi: 10.1159/000503273.

12. Metko D, Mehta S, Mcmullen E, et al. A systematic review of the risk of cutaneous malignancy associated with ultraviolet nail lamps: what is the price of beauty? Eur J Dermatol. 2024;34(1):26-30. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2024.4616.

13. Schmidt SAJ, Schmidt M, Mehnert F et al. Use of antihypertensive drugs and risk of skin cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(8):1545-54. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12921

14. Pedersen SA, Gaist D, Schmidt SAJ et al. Hydrochlorothiazide use and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer: A nationwide case-control study from Denmark. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(4):673-681.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.042

15. Cooper SM and George S. Photosensitivity reaction associated with use of the combined oral contraceptive. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(3):641-2. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04111.x.

16. Moore DE. Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2002;25(5):345-72. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225050-00004.

17. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Artificial Nails: Dermatologists’ Tips for Reducing Nail Damage. https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/nail-care-secrets/basics/pedicures/reduce-artificial-nail-damage. Accessed August 7, 2024.

18. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Gel Manicures: Tips for Healthy Nails. https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/nail-care-secrets/basics/pedicures/gel-manicures. Accessed August 7, 2024.