Ocular Melanoma Risk Factors

Who gets ocular melanoma?

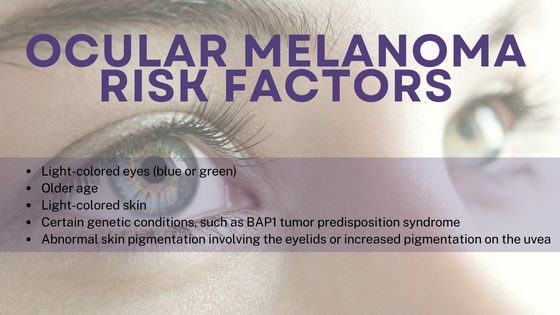

Ocular melanoma is rare, accounting for only about 3 to 4% of all melanomas. It can affect people of any gender, age, ethnicity and racial background. Some groups are at greater risk for ocular melanoma than others. The risk increases as people get older, and ocular melanoma is more common in people with fair skin and light eyes and in people with certain inherited medical conditions.

Who’s most at risk and why? What are the risk factors for ocular melanoma?

The cause of ocular melanoma is not known, but several risk factors have been identified.

Risk increases with age. It is slightly more common in men than in women.

Ocular melanoma is more common in people with fair skin, frequent sunburns, and/or light-colored eyes. It is about 8 to 10 times more common in people of Caucasian descent compared with people of African descent. Although the risk factors for uveal melanoma are generally similar to the known risk factors for skin melanoma, uveal melanoma is not thought to be caused by the sun.

People who work with welding may be at higher risk for ocular melanoma.

Certain inherited medical conditions are linked to having a higher risk of ocular melanoma. People with ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis (pigmentation around the eye and forehead, also called Nevus of Ota) have a higher risk of uveal melanoma, while those with primary acquired melanosis or conjunctival nevi are at higher risk for conjunctival melanoma.

Exposure to UV rays from the sun is a well-known risk factor for skin melanoma. There is some evidence linking UV exposure to some of the subtypes ocular melanoma (possibly uveal melanoma of the iris and conjunctival melanoma), but the majority of ocular melanomas are not linked to UV exposure. Having a skin melanoma does not appear to increase the risk of having ocular melanoma.

If you have none of the risk factors listed above, the American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends that you get a baseline eye disease screening at age 40. If you have any of these risk factors, make an appointment with an ophthalmologist for a comprehensive eye exam.

*Note that benign choroidal nevi are very common, and only a minority may become cancerous

Is ocular melanoma hereditary?

Uveal melanoma can run in families, although this is not common. Hereditary uveal melanoma is caused by specific inherited DNA errors, called mutations. There is a well-known link between uveal melanoma and errors in a gene called BAP1 that can be passed down in families. BAP1 syndrome is often suspected when patients and family members have increased incidence of the following cancers: uveal melanoma, skin melanoma, mesothelioma (lung cancer caused by asbestos), meningiomas (benign brain tumors), kidney cancers, and gallbladder cancers. Other gene mutations that are passed down through families, including mutations in the PALB-2 and MBD4 genes, are also linked to uveal melanoma.

There may be a genetic component to conjunctival melanoma, but because this type of eye melanoma is so rare, less is known about its hereditary causes.

Can the spread of ocular melanoma be predicted?

The size and location of the original melanoma and certain genetic features can help predict how likely ocular melanoma is to spread. Larger tumors are at higher risk of spreading than smaller tumors.

Among uveal melanomas, the location of the melanoma within the uveal tract is linked to how likely the tumor is to spread. Iris uveal melanomas are rare (less than one in 20 uveal melanomas) but are less likely to spread to other parts of the body compared with uveal melanomas that develop in other parts of the eye (ciliary and choroidal uveal melanomas). While up to 20% of ciliary and choroidal uveal melanomas spread to other parts of the body within five years, only about 5% of iris melanomas become metastatic within the same time period.

Doctors may recommend a biopsy of the uveal melanoma to give a better picture of the molecular features of the specific melanoma and help predict the risk of spreading. A type of laboratory testing called gene expression profiling (GEP) is sometimes used to categorize uveal melanomas based on their risk of spreading. Tumors categorized as being highest risk (Class 2) may be up to 20 times more likely to spread than those categorized as lower risk (Class 1A or Class 1B). In addition, certain individual gene changes, or mutations, are linked to uveal melanoma spreading. For example, metastasis is more likely for people with mutations in the BAP1 gene than those without such mutations. Certain chromosomal changes are also linked to metastasis including loss of chromosome 3 and amplification of a part of chromosome 8. There are other mutations seen in the primary melanoma such as SF3B1 and EiF1AX that may also predict behavior of uveal melanoma.

Doctors can use the genetic testing results together with other characteristics of a uveal melanoma (like tumor size and location) and the patient (like age) to help determine how to manage patients after the diagnosis of melanoma. These factors help doctors and patients decide on the type and frequency of follow-up needed to check for the appearance of metastasis after treatment.

Compared with uveal melanomas, conjunctival melanomas are uncommon but tend behave more like skin melanoma after initial diagnosis. Due to the rarity of conjunctival melanoma, less is known about factors that predict the spread of this type of ocular melanoma. Clinical features that have been linked to conjunctival melanoma metastasis include having a larger tumor (thickness > 2 mm), having a tumor that is growing in a nodular pattern, and having melanoma growing in certain areas of the eye including the nonbulbar conjunctiva, medial bulbar conjunctiva, caruncle, or plica semilunaris. In patients with larger tumors (over 2 mm) or tumors with other adverse features, sometimes a procedure is done to determine whether the melanoma has spread to a nearby lymph node. This procedure is called sentinel lymph node mapping and biopsy. Should the melanoma be found in the lymph node, patients may then be recommended for additional treatment to try to prevent further spread. A biopsy for genetic information may also be done to help doctors get more information about the tumor and possible treatments. Conjunctival melanoma may have similar mutations to skin melanoma, such as BRAF, which can be a target for treatments.