Genetic Testing Performed in Melanoma

A Q&A with an Investigator at the National Institutes of Health

Dr. Michael Sargen M.D. is an Assistant Clinical Investigator in the Clinical Genetics Branch and Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the National Cancer Institutes, which is part of the National Institute of Health. He completed his M.D. at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and then a dermatology residency at Emory University in Atlanta and a fellowship in dermatopathology at Stanford University in Stanford, California. His research focuses on melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer, looking into prevention, environmental or genetic risk factors, and biomarkers. He frequently publishes literature describing inherited mutations among cancer-prone families.

AIM at Melanoma interviewed Dr. Sargen, who is leading a clinical study (NCT00040352) to investigate how genetic and environmental factors contribute to the development of melanoma. The link to the study details, including eligibility, exclusion, and inclusion criteria, is here: https://clinicalstudies.info.nih.gov/ProtocolDetails.aspx?id=02-C-0211

Footnotes in this interview provide further reading material on the concepts in Dr. Sargen’s answers.

What is genetic testing?

MS: Genetic testing is a laboratory test that evaluates for genetic alterations that increase risk for specific conditions such as cancer. This testing often involves analyzing genetic material, also known as DNA, extracted from blood or saliva.

What is the role of genetic testing in skin cancer?

MS: Genetic testing can help identify individuals who may be genetically predisposed to developing skin cancer. Individuals who are at elevated risk can benefit from increased skin surveillance by a dermatology healthcare provider. Skin changes that are associated with cancer can then be identified at an early stage and removed.

Does genetic testing occur among families at high-risk for melanoma?

MS: In the United States, we generally recommend genetic testing for families in which three or more members have been diagnosed with melanoma.1,2 However, other factors may impact genetic testing decisions, including age at melanoma diagnosis in affected family members and other types of cancer in the family that might suggest a specific cancer predisposition syndrome. It is best to discuss genetic testing with melanoma specialists in dermatology, oncology, or clinical genetics to determine whether or not testing is appropriate.

Among individuals with a melanoma predisposition syndrome*, many dermatologists perform skin exams every 6-12 months over the course of their lives with initial exams starting around the onset of puberty. However, the frequency of skin exams can vary based on other risk factors including whether or not a person has previously had a melanoma and their prior history of sun exposure including the use of tanning beds. Dermatologists will consider all of these factors when developing a surveillance plan.

Individuals who carry alterations in certain high risk melanoma susceptibility genes can also be at elevated risk for other types of cancer. For this reason, genetic testing can potentially identify individuals who may benefit from other types of surveillance besides skin exams. For some individuals, the potential anxiety associated with knowing of their genetic predisposition to cancer may outweigh the potential benefits of testing. It is best to discuss these concerns with a genetic counselor before pursuing testing.

What is Protection of Telomeres 1 (POT1)?

MS: Your genetic code is packaged together into discrete units called chromosomes. The Protection of Telomeres 1 (POT1) gene codes for a protein that protects the ends of chromosomes, also known as “telomeres,” from damage during cell division. Loss of POT1 activity due to a variation in the gene can lead to chromosomal damage, which can result in a cascade of genetic events that contribute to cancer formation.

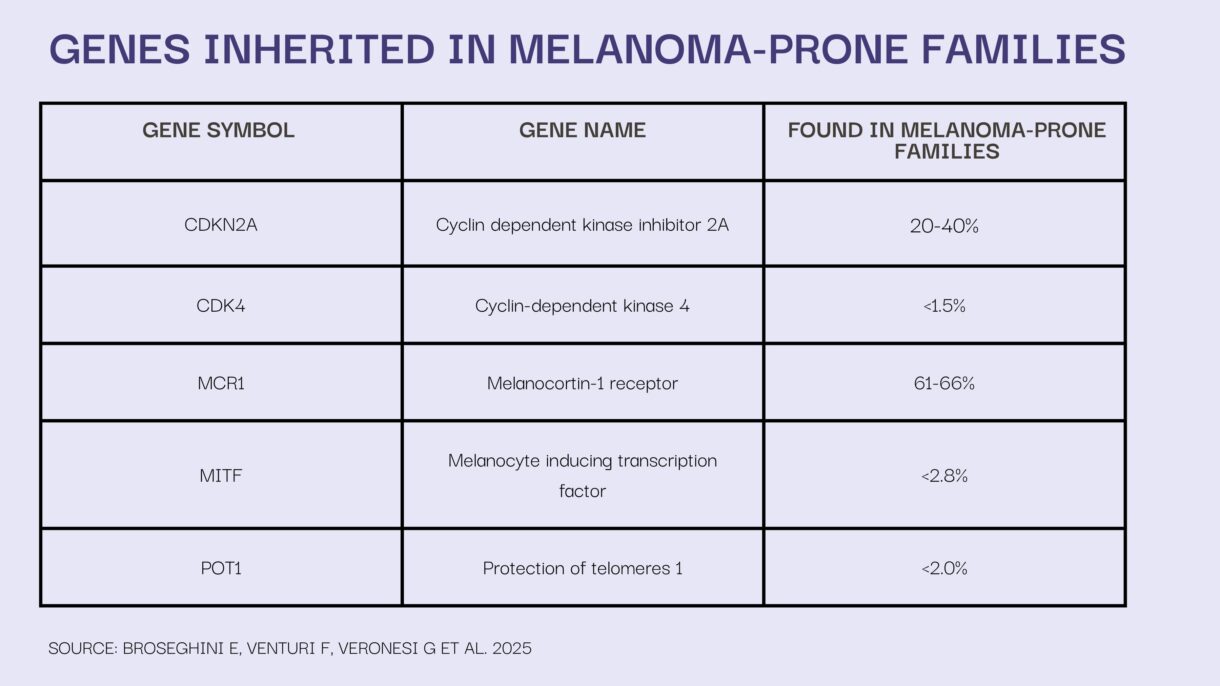

Besides POT1, what other genes are a part of a high-risk panel for familial melanoma?

MS: The most commonly altered gene in melanoma-prone families is CDKN2A—about 20-30% of US families with familial melanoma carry a variant in CDKN2A. Other less commonly altered genes in <2% of melanoma-prone families include CDK4, BAP1, TERT, ACD, and TERF2IP. These genes are often included on melanoma testing panels.

There are additional genes (e.g., TP53, PTEN) that increase risk for melanoma, but melanoma is often not the predominant cancer type in these individuals/families.

Why does the gene POT1 matter with regards to melanoma?

MS: Individuals with a harmful variation in the POT1 gene appear to have a substantially increased risk for melanoma of the skin, compared with the general population.3,4 Therefore, it is important to identify affected individuals early in life so they can receive routine skin surveillance to detect melanoma at its earliest stage when it is most treatable.5

POT1 mutations have been associated with the development of spitzoid melanoma, a rare subtype of melanoma. Harmful variants in POT1 also appear to contribute to other cancer types, including chronic lymphoid leukemia, glioma, and angiosarcoma.6-8

If an individual carries the disease-causing variant for POT1, describe the evidence associated with the risk for early-onset of cancer.

MS: Multiple studies have identified associations between disease-causing variants in POT1 and an increased risk for melanoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, glioma, sarcoma, and potentially other cancers.3,4,6-9 While these cancers appear to have an earlier onset in individuals with a POT1 variant, compared with the general population, larger population studies are needed to confirm this. Determining when to begin screening for a specific cancer type is dependent on multiple factors including the earliest age of diagnosis for that cancer in the family and whether the individual has additional risk factors for disease.

*Melanoma Predisposition Syndrome – An inherited or family cancer syndrome occurring when you have a genetic mutation(s) which increases the chance of developing melanoma, compared to individuals without a mutation.

References:

- Leachman SA, Carucci J, Kohlmann W et al. Selection criteria for genetic assessment of patients with familial melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(4):677.e1-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.03.016.

- Leachman SA, Lucero OM, Sampson JE et al. Identification, genetic testing, and management of hereditary melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017;36(1):77-90. doi: 10.1007/s10555-017-9661-5.

- Shi J, Yang XR, Ballew B et al. Rare missense variants in POT1 predispose to familial cutaneous malignant melanoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):482-6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2941.

- Robles-Espinoza CD, Harland M, Ramsay AJ et al. POT1 loss-of-function variants predispose to familial melanoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):478-481. doi: 10.1038/ng.2947.

- Sargen MR, Pfeiffer RM, Elder DE et al. The Impact of Longitudinal Surveillance on Tumor Thickness for Melanoma-Prone Families with and without Pathogenic Germline Variants of CDKN2A and CDK4. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(4):676-681. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1521.

- Speedy HE, Kinnersley B, Chubb D et al. Germ line mutations in shelterin complex genes are associated with familial chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;128(19):2319-2326. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-695692.

- Bainbridge MN, Armstrong GN, Gramatges MM et al. Germline mutations in shelterin complex genes are associated with familial glioma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;107(1):384. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju384.

- Calvete O, Martinez P, Garcia-Pavia P et al. A mutation in the POT1 gene is responsible for cardiac angiosarcoma in TP53-negative Li-Fraumeni-like families. Nat Commun. 2015:6:8383. doi: 10.1038/ ncomms9383.

- Savage SA. Telomere length and cancer risk: finding Goldilocks. Biogerontology. 2024;25(2):265-278. doi: 10.1007/s10522-023-10080-9.