Valerie Guild, AIM President: A Mother’s Love Shines Light on Melanoma Treatment, Cure

By Vallerie Malkin

2019

It wasn’t right that Charlie Guild lost her battle with melanoma at 26. But in terms of the positive impact her story would have on the melanoma community, she had the right mother.

What stunned Valerie Guild from the moment her daughter was diagnosed was the lack of treatments available—and the absence of any on the horizon.

Reputable oncologists who treated melanoma existed across the country, but according to Guild, “Many told me there was a lack of collaboration that was hindering progress on fighting the disease.”

Equally shocking was the painstaking and often futile process of searching for accurate information on melanoma in 2003, according to Guild. There was no comprehensive website or any authoritative source of information. The family found that every time they talked to a new person in the medical community, they just ended up having more questions.

Instead of a cohesive narrative around melanoma, with structures for support, philanthropy, and research, Guild found that information was fragmented and disconnected, and the cure was a distant hope.

“It was agonizing,” says Guild. “There was nothing we could do but watch her die.”

Ardent Resolve

Guild vowed to devote the rest of her life to reversing the dismal course of melanoma. Her grief became a fierce determination to find out why melanoma lagged so far behind other cancers in terms of research and to solve those issues in order to jumpstart a renewed search for the cure.

“Defeating the cancer that took my daughter’s life became my life’s work,” says Guild.

She also vowed to provide families with up-to-date and comprehensive information on melanoma—to be the resource she searched for in vain.

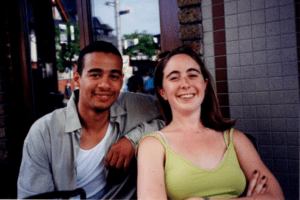

Who was Charlie Guild?

To understand Val Guild’s determination, you only have to know she is a mother who lost a daughter. But Charlie’s personality also helped shape that determination.

“Charlie wanted to give back,” recalls Val Guild. “She loved helping people. She hoped to have a life that would be in service to people.”

Charlie was an academic achiever who studied neuroscience and Russian literature at Brown University. After college and a stint on Wall Street, she asked her employer for a transfer to the San Francisco office to be closer to family. She was considering medical school.

It was about this time that she told her mother she had a pain in her chest. After an x-ray revealed nothing unusual and the pain subsided, Charlie resumed her work, only to be hit with worse pain several months later. This time a scan was ordered, and the results were devastating.

It was about this time that she told her mother she had a pain in her chest. After an x-ray revealed nothing unusual and the pain subsided, Charlie resumed her work, only to be hit with worse pain several months later. This time a scan was ordered, and the results were devastating.

“I will never forget that moment when the doctor told us it was Stage IV melanoma,” Val said. Soon they learned just how bad the prognosis was: Viable treatment options were non-existent, and late-stage melanoma was nearly always a death sentence.

The diagnosis was devastating for everyone in the family, and of course earth-shattering for Charlie herself. “Charlie was in love with her life,” Guild says. “She was intellectually fearless, but she was not fearless about dying. None of us is, I expect.”

Charlie announced that she would choose to live the remainder of her life focused on the present, while her family focused on how they were going to manage her treatment. Her choice turned out to be a blessing.

“Charlie lived the remaining months of her extraordinary life on her terms, something we continue to be grateful for,” says Guild.

First Things First

After her daughter’s death, Guild created the Charlie Guild Foundation, which would later become AIM at Melanoma. Then she set off around the world to speak with melanoma experts, asking them point-blank what was needed to propel their research.

Surprisingly, she heard one statement over and over again: We need fresh frozen primary tumor tissue; we need a critical mass of it, from a variety of patients; we need the patient data; and we need to collaborate on the research.

But they also told her collecting fresh-frozen primary tissue was nearly impossible to accomplish, from the relatively small number of melanoma tumors removed in hospital settings, to the need for freezers and protocol in those settings, to the complicated process of getting individual research institutions to work with each other on the tissue research.

Feeling defeated before she had barely gotten started, Val recalibrated, and she allowed her penchant for problem-solving and her natural calm guide her.

Guild then met with Dr. Mohammed Kashani-Sabet, a melanoma researcher working in nearby San Francisco, and it was he who suggested she pursue the creation of a fresh-frozen primary tissue bank, with multiple branches around the world. He knew how valuable it would be to research, and he realized after sitting with her for only a short time that she was the type of person who could make a tissue bank a reality, even if it took many years. What’s more, he told her, he would sign on to help if she moved forward.

Guild hesitated, at least momentarily. Her background made her an odd match to create the missing link in melanoma research. She wasn’t a scientist; she was a CPA. Guild and her husband owned a financial services company, and she still had two daughters to raise.

Then she thought of Charlie and said, “Yes.” But she would soon find out she had a lot to learn.

Melanoma Is Different

Researchers will tell you it is the primary tumor that holds the entire genetic code. Studying primary tumor tissue—when it has been fresh-frozen and the DNA and RNA are preserved, and when there is comprehensive patient data accompanying it—is key to understanding how cancer spreads and why.

In so many cancers, this process of removing and freezing primary tumor tissue, collecting data, and then studying both has been relatively straightforward: The patient comes to the hospital for inpatient or outpatient surgery; data and consent are collected; the tumor is removed, frozen, and studied. Breakthroughs in understanding and treating breast cancer and prostate cancer, particularly, can be traced to studying fresh-frozen primary tissue.

But melanoma is challenging in so many ways, beginning with a problem absent in other cancers: Melanoma tumors are usually removed in a dermatologist’s office, not in a hospital surgery setting. Because of this locational circumstance, the tumors are not frozen, critical patient data is not recorded, and the chance to study that primary tissue is forever lost.

Guild had her work cut out for her.

Who Is In?

Val resumed her world travel schedule, meeting again with some of the same experts in the field to discuss her goal of creating a global tissue bank. There was extreme interest, of course, and a good deal of surprise that this rather petite woman intended to solve a giant problem in melanoma research.

Soon she had gathered a handful of researchers and institutions to commit to the tissue bank. She named the initiative the International Melanoma Tissue Bank Consortium (IMTBC) and began discussions and negotiations to bring the institutions into agreement on how to run this collaborative, global tissue repository.

Months turned into years. Every step of the process took longer than she imagined and involved more detail—and attorneys—than she ever thought possible.

“Human tissue—and the handling of human tissue—are both highly regulated and not regulated at all,” Guild noted. “The legalities surrounding things like consent of the patient, intellectual property rights, and storage, just to name a few, are extremely complicated. And because we were dealing with institutions in different states and different countries, the complications multiplied exponentially.”

Guild was in uncharted territory. But she pushed on, with the support of the researchers at the tissue bank sites, one of whom was Dr. John M. Kirkwood, M.D., at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center at the University of Pittsburgh, whose site was slated to open first. Kirkwood and Guild talked regularly about IMTBC and melanoma, and from these conversations, a new project was conceived.

Years earlier, just after Charlie’s death, they had discussed the frustrating lack of collaboration and communication among the world’s melanoma experts. They both believed there was a need for an informal gathering of a relatively small group of melanoma experts to share data, discuss ideas, and plan collaboration—a meeting above and beyond the formal, presentation-style conferences that many researchers already attended. Additionally, they believed researchers would benefit from interacting informally with pharmaceutical companies, and vice-versa.

Guild proposed that she host just such a meeting and that Dr. Kirkwood be her co-chair. He agreed.

She immediately planned a date, sought grants, and invited 25 of the world’s leading experts in melanoma to discuss how they could move the needle on the search for the cure.

The inaugural meeting in 2011 was so successful the researchers asked that Guild not only commit to hosting it again but that she host it bi-annually. She agreed, and the International Melanoma Working Group (IMWG) was born.

But There Was More For Her To Do

Val Guild’s vision was nowhere near complete. While research to end the disease was her number one goal, she also knew she had to solve the education and resource issue that so affected her family’s quest for information while her daughter, Charlie, was ill.

Guild wanted to offer patients and families one place to go when they were diagnosed, a website that was comprehensive, up-to-date, and accurate. She wanted to create the website that she sought—in vain—when Charlie was diagnosed. “I remember thinking that it certainly would help if information and resources could be pulled under one roof,” says Guild. “And I was determined to create just that.”

In 2009 the AIM at Melanoma website, a hub of informational, educational, and advocacy resources for melanoma patients and their families, debuted to the public. The site has been redesigned three times over the years, including just recently, each time adding more and more resources that benefit the melanoma community. Indeed, the website is widely considered the most comprehensive melanoma site, with an average of 52,000 visits every month. As was Val Guild’s goal, people visit the site to find the kind of information that was not available when she needed it the most, after her own daughter’s diagnosis.

Finally, An Announcement

Meanwhile, the tissue bank discussions, negotiations, and challenges continued. As Dr. Kashani-Sabet predicted, it took many years to convince institutions to give up their IP rights; to standardize patient data collection; to share data; to create the legal framework around the tissue banking concept.

But just over 15 years after her first “world tour” asking researchers what they needed to battle melanoma—on April 5, 2019, what would have been Charlie’s 42nd birthday—AIM at Melanoma issued a press release announcing the grand opening of the first branch of the International Tissue Bank Consortium under the watchful eye of Dr. John Kirkwood, at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

On September 9, 2019, the second branch of IMTBC opened at CPMC San Francisco, with Dr. Kashani-Sabet at the helm. The other four locations have agreed to their contracts and are finalizing details. These branches should all open shortly.

A singular achievement that will have remarkable results in the long term for melanoma patients, the IMTBC is the first collaborative fresh-frozen primary tissue bank for melanoma in the world, enabling the study of fully annotated fresh primary tissue that is key to understanding the genetic codes of the disease.

With four U.S. locations and two international sites, the IMTBC is unique in its critical-mass approach; the goal is to collect 500 primary tumors within two years, and researchers from anywhere in the world may apply to study the tissue or data or both.

Making the Connections

Through her work, Guild has met countless melanoma patients, survivors, and families. For Guild, the connections provide a sense of renewal and even more purpose for continuing her work. For those she meets, the connections provide myriad ways to get involved.

Some survivors and families have testified before their local legislators to induce lawmakers to ban tanning bed use for minors—another of AIM’s major objectives that has contributed to bans in 17 states. Others coordinate or volunteer at AIM’s fundraising walks across the country. Still others take AIM’s prevention and early detection messages to their own communities. All want to help eradicate the disease.

“It is remarkable to me how motivated people are when they have this disease to fight it, as well as how willing they are to give back and to support AIM in finding the cure,” says Guild.

A Marriage of Heart and Science

Charlie Guild’s story anchors the foundation and infuses every aspect of the work of the AIM team. The non-profit has grown to include seven employees, all of whom share Val Guild’s can-do attitude and her desire to see the disease cured. One of those employees is her oldest daughter, Sam, who gave up her career as a corporate attorney to work for AIM.

By doing something positive with their loss, the Guilds have honored Charlie’s desire to give back in the most meaningful way possible.

“I know Charlie would be proud of this work and AIM’s accomplishments,” says Guild. “She would love what AIM has done for the melanoma community.”

But this mother is not ready to rest.

Last year, the U.S. saw an estimated 96,480 new cases of melanoma and 7,230 deaths from the disease. While the number of deaths is decreasing due to giant strides in research in the last few years, the incidence rate continues to climb.

“There is much more work to be done,” Guild says.

UPDATE:

On May 21, 2020, AIM at Melanoma lost Founder & President, Valerie Guild. She died of complications from cancer.

Recent Posts

Behavioral Addiction Responsible for Excessive Indoor Tanning

Announcing AIM at Melanoma’s Official Sunscreen Partner, WearSPF

Red Hair Genetics: 5 Things You May Not Know

Surviving & Thriving: From Melanoma Survivor to Sun Safety Advocate